I was one of two Communications Specialists activated with Nebraska Task Force One. We manage task force radio communications, PBX telephone system, and a variety of other tasks as needed.

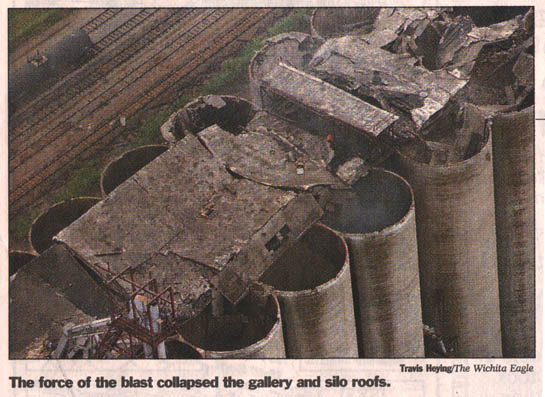

The DeBruce elevator is the largest grain elevator in the world, fed by a single head house. There are 267 silos, arranged in three rows, each 120 feet tall, in a complex stretching over half a mile in length. The total capacity of the elevator is approximately 20 million bushels. The explosion is considered to be one of the worst grain dust explosions in history. All of the fatalities from grain elevator explosions in 1998 occurred in this one accident. 11 people were injured, and seven died in the explosion. Immediately after the explosion, it was believed that there were possibly 4 people trapped in the tunnels under the elevators.

This dust explosion was unusual in that it appeared to propagate through almost the entire complex, both in the tunnels below, and the structures across the top of the silos. It appeared that almost no part of the elevator was untouched by the explosion. Many of the silos had their tops blown out. A prime example of the force of the explosion was a heavy steel door which covered one of the tunnel entrances, approximately 7 feet by 7 feet, weighing about 600-800 pounds, which was missing. Initially rescue workers wondered where it had gone, until someone looked up...and saw that it appeared to be "shrink-wrapped" into the I beams of the gallery floor 120 feet straight up!

Ironically, a fire safety inspection was due just minutes before the explosion took place, at 10:00 A.M. This undoubtedly would have lead to the injury or death of even more people, had the explosion taken place a few minutes later. There were stories of other narrow escapes as well, such as that of a truck driver, who was loading grain, and at the instant of the explosion, saw a 500 pound motor fly past his windshield. All the glass was blown out of the truck cab, but he escaped with minor cuts and bruises.

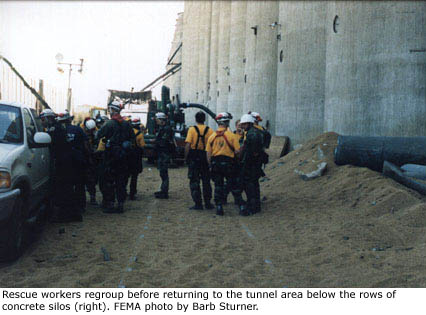

After local authorities worked ferociously for hours to try and reach the remaining four victims in the tunnels, it became obvious that conventional rescue techniques were not working. Most of the doors that allow grain to be emptied out the bottom of the silos, were blown off by the explosion, and the tunnels had largely filled with grain. As the grain was removed, more poured in out of the silos, and reaching the victims was impossible. A decision was made to call in a FEMA USAR team to assist in the rescue. The closest was in Lincoln, Nebraska. The team was paged at 4:00 P.M.

We arrived at the police check point about a mile from the scene at about 1:30 A.M. As we approached the site, there was a concentrated area of illumination, surrounded by the largest collection of emergency vehicles I have ever seen. There was the smell of smoke in the air from the dozens of fires still burning in the silos, and the dark silhouette of the elevator complex was just to the east. Many exhausted rescue workers were sleeping out in the open on cots.

We immediately began unloading our equipment, and setting up base camp on a large concrete slab about 100 yards from the elevator. As the camp quickly began to take shape, we issued radios to all team members. The radios are Bendix/King 5-watt, narrow band portables. They come with speaker/mics. They operate in the frequency range of 402-420 Mhz. We had one assigned simplex frequency, and one repeater pair. Initially the radios were all used in simplex mode, until the portable repeater could be set up.

Much to our dismay, we found that the portable repeater had somehow been left behind. We quickly improvised using two handheld radios, a gel-cel 12v battery, two clamshell battery cases, and a spare repeater controller box. We soldered pigtails on the clamshell battery packs, and connected power to the unit. It worked perfectly.

It was only a 5 watt output repeater, but for a two mile radius, it did most of what we needed. A shipping container made a makeshift enclosure. We used a pair of portable masts to mount receive and transmit yagi antennas. We selected a site as close as possible to the rescue operations site, and also in sight of the base camp. The massive steel and concrete structures of the elevator created some real problems with getting signals everywhere we needed. The crews working in the tunnels were virtually unable to make the repeater, so they operated simplex within their groups, and used a man at each tunnel entrance as a relay to the repeater. Even so, the effectiveness of the communications system was not as optimum as we would have liked.

Besides the radio system, a phone system had to be set up and maintained. We had a portable phone switch, which was connected to the outside phone network on the first day. Two satellite cell phones were also set up in the Command Tent. All power was supplied by our portable generators.

Once our main task of setting

up all the communications equipment was taken care of, we also assisted

in other odd jobs such as shuttling personnel and materials, being messengers,

changing hundreds of handheld radio batteries at each shift change, and

whatever else needed done. We worked in alternating 12 hour shifts,

with half the crew on duty at any time. Often we all continued working,

well after our shifts were over, especially if there were any tasks still

needing completion. Many people worked straight through the first

24 hours, myself included. We did not have showers available for

the first two days, and in the Kansas summer heat, we began to not need

insect repellent. People from the local area would come up to us

and thank us for coming to help, all the while holding their noses.

The first night we took a short nap inside one of the damaged warehouses.

The second night, they opened a local school for us to use as living quarters

during our rest shifts, and finally--showers!

In walking around the silo complex, I noticed that almost every silo had huge cracks, as though the walls had "flexed" during the explosion. There was some concern over some of the structure collapsing, so "crack sensors" were applied to the cracks in the area where the extrication operations were taking place. These devices sense minute changes in the cracks, and give an audible warning if change is detected.

After the shoring technique

was perfected, and significant progress was made clearing the tunnels,

and more openings were cut into the tunnels, through 18 inch reinforced

concrete. Partial remains of one elevator worker was uncovered, and

later two more. Fires still burned in numerous silos for days, as

it was feared that trying to spray them down with water might stir up more

dust and cause more explosions. Since they were contained in flameproof

concrete containers, they were allowed to burn. It wasn't until many

weeks later that the fires were actually all extinguished.

At the time I remember feeling like I had taken over someone else's life. The sudden and unexpected shift from normal life to living at a disaster scene. It was also strange to see news reports on CNN about something I was personally involved in. Reporters hung out just outside the police check points. Soon we realized that the media had found our com frequencies, and were reporting developments faster than we could inform the local authorities, which was creating some problems. Our crews then started using codes over the radios to prevent information leaks. It wasn't that we needed to conceal information, it was that we needed to inform the proper local authorities first. We didn't want the families of victims hearing that they had lost a family member from the media first, and so on. Our use of radio codes did not stop the information leak for long, as apparently later one of the local fire rescue crew members had brought in a cell phone and was reporting information without authorization.

There was one little bit of humor that took place, as we were going through the police checkpoints from time to time running errands. The local Sheriffs cars had big lettering on the sides of their cars which spelled out "SHERIFF". Whenever a deputy would stand next to the car with the door open, the "S" went out of sight, and the letters then spelled "HERIFF". I couldn't resist pulling up to a deputy and saying "Hey, what's a HERIFF?" He looked puzzled for a moment, then looked at his car, and burst out laughing.

Rescue operations had to be halted twice due to severe weather. At one point we were under a tornado watch. The main concern was the hazard of debris blowing off the tops of the silos, and raining down on rescue crews. We did also have two shoring collapses, one of which trapped a rescue worker for a short time, but he was not injured. Strangely, the very same worker was accidentally struck on the head by a falling pipe on the last day. He was knocked unconscious for a short time, and was taken to the hospital, but was treated and released the same day. His helmet saved him.

The USAR team continued its efforts to find live victims for a total of six and a half days. With the overwhelming evidence that the blast was certainly and instantly fatal to all occupants of the tunnels, the decision was made that the time had come to cease operations. The fourth victim remained unfound until six weeks after our mission ended.

In the end, our communications system did its job. There were times when radio communications were not as consistent as we would have liked. As a result we received funding for an elaborate new set of radio equipment, including two 50 watt portable repeaters, a 50w UHF base station, a 50 watt VHF base station, solar panels for remote charging of repeater batteries, new low loss coaxial cabling, new antennas, and we also have two HF radios on order. More communication enhancements are also planned for the future.

In spite of our massive effort, no lives were saved, but at least the families of the victims had no more doubts as to the fate of their loved ones. Our efforts were successful in that there was closure for the families of the victims, and we completed our mission and returned home, with no rescue worker deaths or serious injuries.

According to one recent article, the ignition source of the blast was believed to be a failed conveyor belt bearing...one of 12,000. OSHA has proposed a 1.7 million dollar fine against the DeBruce Grain Company for gross safety violations. I was told by a Wichita fireman that on a safety inspection just three months previously, he had felt very fearful to even be in the elevator, because of the extreme amount of dust contamination, but the inspection was only for training purposes, and that they had no jurisdiction at this elevator.

Greg Trook

For additional photos and

newpaper headlines, click

here. (Please be patient as the images take time to load).

For more information, see the FEMA web page on the DeBruce elevator explosion: